Dagboek 1/n: Something In The Distance

Evenings in the flatlands, urban loneliness & an old neoliberal party trick.

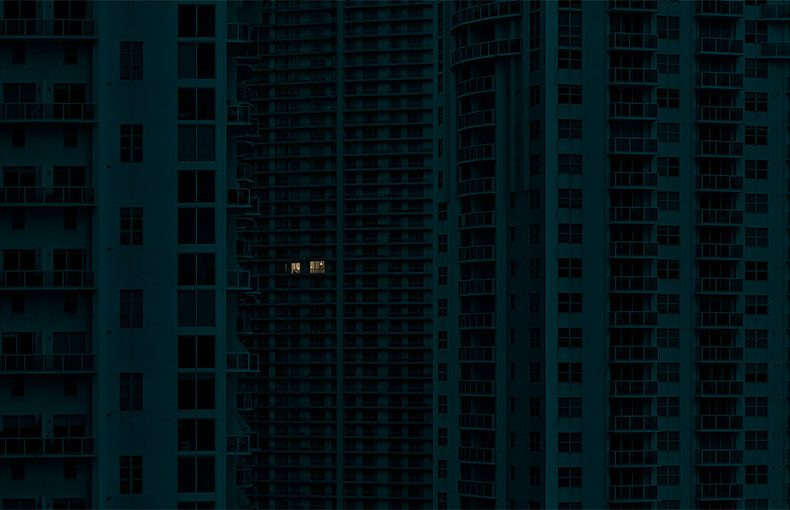

Sometime in November last year, I visited The Hague — known for its imposing architectural downtown surrounded by the orchestra of footsteps ascending and descending trams, its footpaths narrowing into buildings of government and the chilly afterglow of its winter-wind. I had been visiting Abhiraj who studied in the city, after having taken the 803 from Brussels-North (or Brussels-Noord, if you're a local) through a two hour-and something journey from the Belgian capital past the apathetic welcome of Rotterdam's windmills. All I had seen through the journey were the green agricultural flatlands that occasionally gave way to a beer factory or two, and convoys of cross-country trucks, mini-vans and half-hearted rain spat out by the gray loneliness of surveilling European clouds. Even as the bus rushed past the executive jostle of Rotterdam's evening-crowd and into the urban music composed by The Hague's automobiles, nothing in the cityscapes of either town changed except the customary histogram formed by the town's skyscrapers. Such is the bane entourage of contemporary metropoles where every architectural nook resembles the exact other, with little to separate between the two destinations — one can even wonder if two metropoli are different destinations at all, as presence in one is experientially alike presence in another. Calvino's Invisible Cities in the contemporary context resembles no longer the desirable architectural and cultural incongruence between two destinations; in fact, there is ever only one great metropolis, and every other is, in some capacity, an imitative rendition of the former. Having grown up in the so-called and oft-exoticized suburbia of the third world, I have allowed myself the perversion of metropolitan sight-seeing as some sort of near-revelatory experience where I am supposed to inhale the grand incumbent revolution of human creation. Barely once have I revoked from myself the masturbatory gaze across the technotronic Eden to be fully enamoured by the cyberpunk of our post-industrial cityscape. Yet, across the maps of every new town-borne city, each time I have only encountered the same emotion: urban loneliness.

Every city I have ever visited in my life has felt lonely. Almost always have I taken great measure to ensure that it is not my contextual isolation that I project onto the stone-and-cement structures that surround me in these metropoli; it is the very nature of the urban landscape itself that breeds these emotions of loneliness. What is it about the urban cityscape that fosters loneliness? In theory, the city should serve to be the highest form of macro-civilization: the most extreme state of total population, saturated within a respective boundary with different factions catering to different elements of an imagined 'total urbanity'. Theoretically, the structural apparatus of a city is such that it becomes virtually impossible to feel lonely, as one can always be spoilt and tempted by options. Yet, the city is the greatest divider and the strictest individualist, breaking each component of life into the latest trend of micro-apartmentism. That evening, as I had been walking back home in the watchful paternal congeniality of my friend against a particularly argumentative Dutch wind, and the bells of some nearby seminary played a melancholic Kathleen, I had felt no different sense of loneliness than I had felt being in my home city, and the loneliness I could assume I would surely feel if I lodged in the cities that passed by my bus window earlier that day. I was in the middle of our civilization's greatest social, yet the disconnection between the elements of The Hague and my person could not be more pronounced.

One can always wax eloquent about a Bernard Tschumi or shake their heads and perform a "hell yeah man, didn't you read Rem Koolhaas' architecture stuff" over a slippery pint at a mid-weekend party, but perhaps the emotional component of urban loneliness is better described through the first person perspective. After all, the FPP would be on brand. The individualizing capacity of the city and its failed promise of engineering togetherness is perhaps the most pronounced duality of our modern economic landscape. What exists in reality are neoliberal billboards of faux-togetherness of a festive season, a summer sale, a Fall Pinterest mood-board... The image of the city — like its documentation itself into digital micro-slices — is a reproducible template that remains, for all intents and purposes, infinite.

In-fact, the function of the modern city is to maintain this dull reproducibility so as to limit emancipation. There are no punk metropolitan cities beyond an obscene proletarian subway graffiti or a chewing gum stuck under a public park bench. By limiting emancipation, the city preserves its market while extending its reach to sites of immanence. The brutalist manifesto of eternal continuity takes pleasure in the knowledge that one day, even the greenest of hills will be laden with red asphalt — a two-lane bike path that rivals the six-lane highway. An image of doom, but with the promise of prosperity — a perfect poem that encapsulates the neoliberal towards productivity, simplicity and sedimentation. The duality of the city gives way to the duality of a higher order, a backchanneled agreement between the moving and the sedentary, both of which occur simultaneously.

Irony dies of boredom in the traffic jam and the city administers its coup de grâce on difference.